Soil-on-chip: a review

Author

Jesús Manuel Antúnez Domínguez, PhD

Publication Date

August 26, 2020

Keywords

Soil-on-chip

Bioremediation

biofilm formation

Chemical heterogeneity

Physical heterogeneity

Need advice for your soil-on-chip system?

Your microfluidic SME partner for Horizon Europe

We take care of microfluidic engineering, work on valorization and optimize the proposal with you

Introduction

In this review, the progress in the field of so-called soil-on-chip systems will be discussed, including some of the most exciting applications already available to this date and some promising areas of research for the future. Soil is a complex environment consisting of minerals, water, gases, organic matter, microorganisms, and plant roots.

All these elements are interconnected in such ways that their interactions shape a heterogeneous yet balanced environment under constant changes.

The challenge to studying this system comes from the fact that, as of today, no direct techniques allow its analysis without fundamental alterations of its properties, and no model has been able to recreate and control the spatiotemporal variations required for a reliable simulation of its environmental conditions. A webinar with further information on the topic is available below.

The potential solution to many of the obstacles that microbial ecology faces in soil research can be found in microfluidics. Not only is the scale of soil structures in the range of application, but also, the reduced quantities of reagents needed, transparency, and the specifically tailored approaches offered by microfluidic systems are valuable advantages that make them fit for this purpose. If interested in this topic, further information can be found in the reviews from [1] and [2].

Reproducing heterogeneity in soil-on-chip models

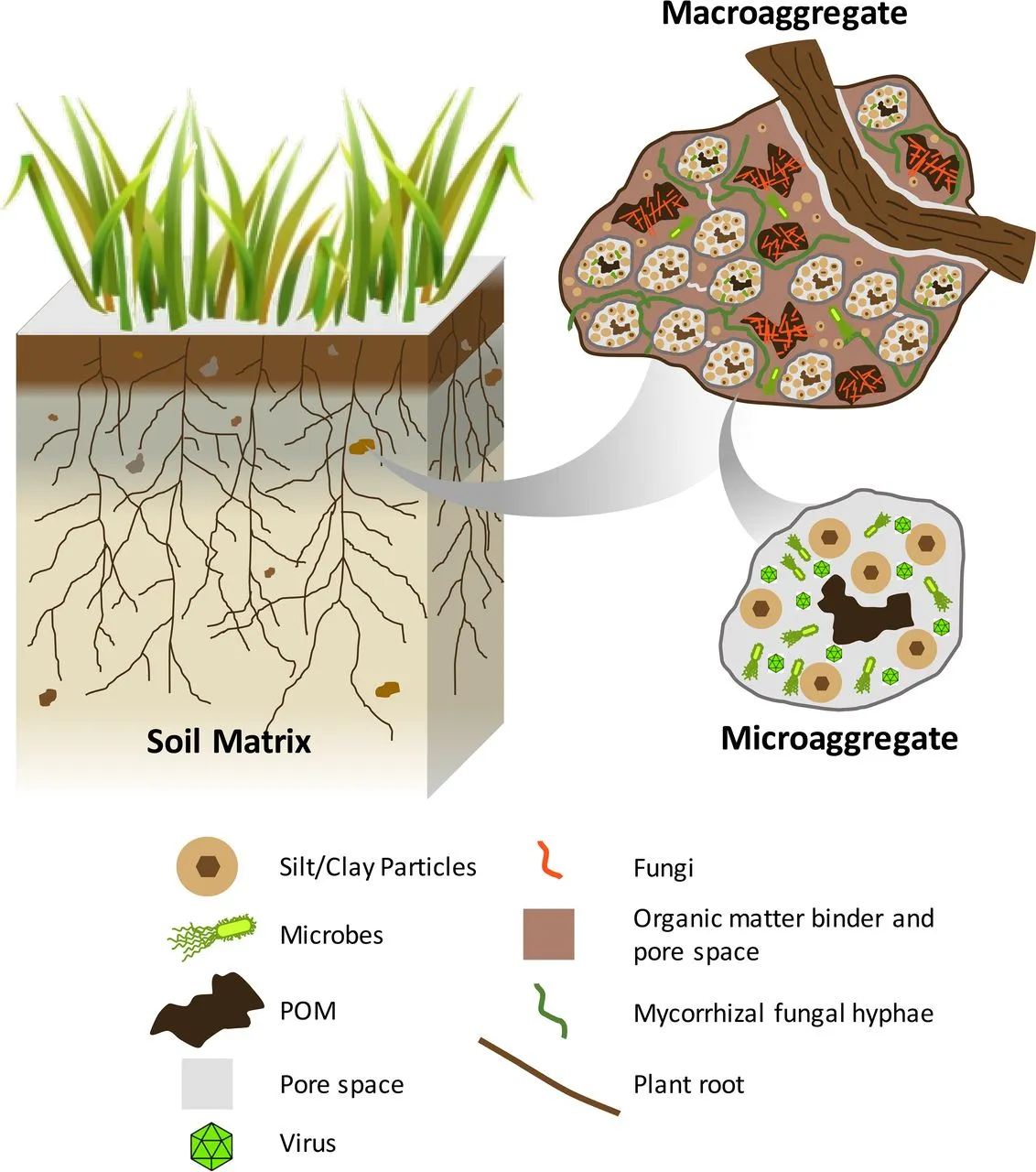

From a structural point of view, the soil is a complex configuration of microaggregates and pores. The microaggregates consist of different types of particles, minerals, or organic matter particles. These microaggregates are held together in macroaggregates by combining electrostatic forces and organic structures such as fungal hyphae and roots [3].

Therefore, it can be stated that the main characteristic of soil is its heterogeneity, which is effective at many levels, and that it can be simulated in different ways with microfluidic models, depending on the focus of the study.

Physical heterogeneity

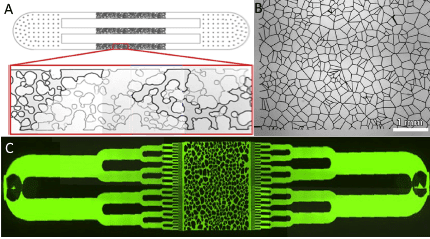

From a physical point of view, the soil has many obstacles and barriers that prevent the free circulation and dispersal of substances and microorganisms. To better understand the transport of entities through the soil medium, an intricate topography of channel pillars and walls of different shapes and sizes can be achieved through microfluidics.

This environment is especially interesting for the research of auto-propelled particles, that is, active matter [4]. Thanks to microfabrication techniques like soft lithography [5] and PDMS casting [6], the specific requirements of a particular type of soil can be tailored according to actual soil samples, allowing complex structures without compromising reproducibility.

Introduction to soil-on-chip systems

Chemical heterogeneity

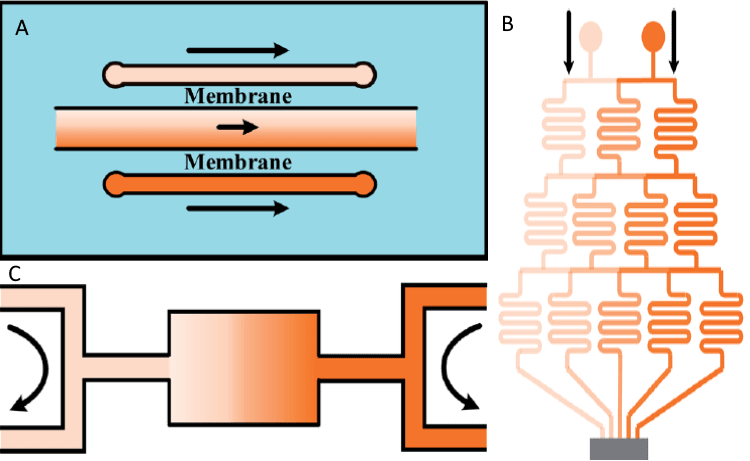

As stated before, soil composition is far from constant, and a wide variety exists of the materials that make up the aggregates and other substances present in the form of gradients and flows. Most of these substances are essential biological resources such as water, nitrogen, carbon dioxide, and oxygen, varying continuously depending on external conditions.

In this regard, microfluidic devices can produce similar gradients through the use of agar blocks (with the drawback of increased opacity) and hydrogels to achieve controlled release or controlling the flow through the use of tree-shaped channel flows, pressure balance (OB1) or membranes [7].

Biological heterogeneity

Soil organisms mainly refer to bacteria and fungi, even though plants and some animals, especially nematodes, must also be considered for a complete system analysis. Traditionally, the culture of microorganisms is focused on a single species to which the physical and chemical requirements of the device are adapted. Nonetheless, in the case of soil-dwelling microorganisms, those requirements also include the presence of another particular set of species that share synergistic metabolism paths or communication, that is, quorum sensing [8].

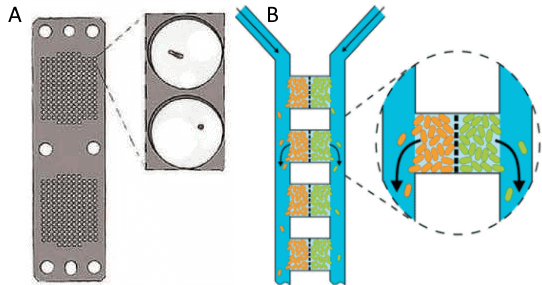

A better understanding of these effects is one of the aims of soil-on-chip systems, so the idea of co-cultivation of several species has been explored through different methods. On the one hand, the option of Individual cultures, in which each cell is confined in its permeable chamber, is explored on isolation chips [9].

The cells and populations are not connected but can access the same medium and the products others generate. On the other hand, a similar microfluidic concept is based on the circulation of each species through different channels but being close together, only divided by membranes [10].

Study of interactions in soil-on-chip models

All the previous types of heterogeneity can be interlinked to combine their effects. These direct interactions between elements of the environment are critical to a more realistic characterization, even including more complex organisms like the roots of plants [11] and nematodes [12].

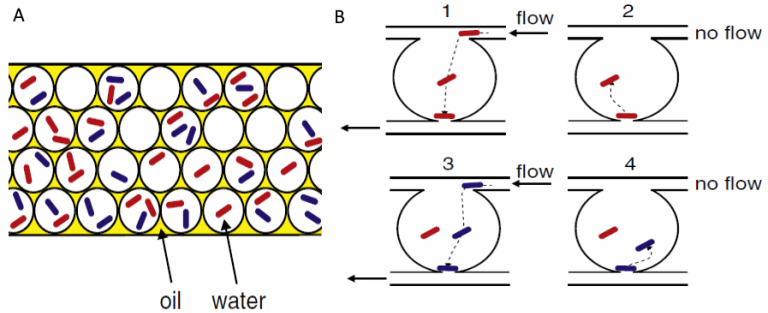

A general approach to analyzing direct interactions uses droplet-based microfluidics, where each droplet is an isolated and complete environment [13]. Depending on its elements, a different stage of development will be reached according to the interactions and relations established.

This technique is beneficial in detecting symbiotic relations [14] as only the direct contact of both species will trigger their proliferation. It is also worth noting that the droplet format provides some advantages, namely, the simultaneous parallel performance of many experiments, sorting droplets depending on the outcome, and more accessible screening and handling.

Alternatively, single-cell trapping also allows direct contact with the present elements and the analysis of possible interactions in a static, isolated environment [15].

Applications of soil-on-chip microfluidic devices

On top of research to understand the soil ecosystem, further applications can be envisaged for soil-on-chip systems. These are derived from the advantage of a controlled environment where every significant parameter can be adjusted accordingly, and previously nonculturable species can be maintained in culture.

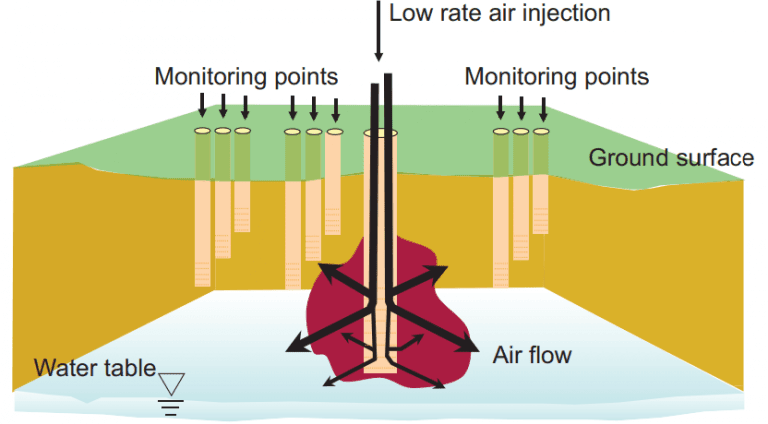

Bioremediation

Soil is an environment susceptible to pollution, but as opposed to water or air, the medium is primarily static, and a thorough detoxification implies its fundamental alteration. A more environmentally friendly and viable option to avoid radical intervention in the ecosystem comes from the possibility of using microorganisms to metabolize the present toxic substances. However, for this process to be successful, the suitable species must be in adequate amounts to access the pollutant and additional resources required for the metabolic pathway.

Natural systems hardly meet these conditions and usually have to be optimized. Consequently, reliable soil models suggest to offer the most efficient solution. Conveniently, there are many soil microorganisms, especially bacteria and fungi [17], capable of degrading substances hazardous to the environment, such as crude oil [18], pesticides, and heavy metals [19].

Biofilms on soil-on-chip

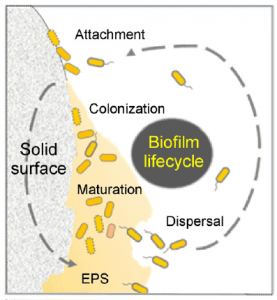

Under the right conditions, microorganisms can associate themselves with supracellular structures known as biofilms, which consist of communities of cells embedded in extracellular polymeric substrates.

The main interest of these structures comes from the fact that the collective behavior of microorganisms can change significantly compared to their free-moving state. Therefore, the substances they produce change, and their survival resources change.

This effect can be further enhanced by associating different species that complement each other inside the biofilm, granting protection against environmental changes and increasing the community’s overall viability.

Microfluidic approaches have successfully formed biofilm for aquatic [21] and marine bacteria [22]. In the case of soil, even if microorganisms are often found in biofilms, microfluidic research is still relatively recent [23].

A better understanding of biofilm formation mechanisms could lead to the culture of many new soil species, which could have critical applications such as bioremediation or the discovery of novel pharmaceutical compounds [24].

Conclusion

In short, the study of soil tries to answer many questions that could be answered through microfluidics. Even if some notable advances have been made, most of the research has been done in recent years, and the proper development of the field has yet to come. Moreover, given the complexity of soil, we are far from a reliable single device that can mimic soil completely.

However, different models adapted for a few specific aspects of this multifaceted environment are being developed. The slow progress of research on this topic can also be linked to the low availability of soil-on-chip devices nowadays, so these new tools will significantly benefit the field by giving access to the required apparatus to a broader audience.

Soil-on-chip review done thanks to the support of the ActiveMatter

H2020-MSCA-ITN-2018-Action “Innovative Training Networks”, Grant agreement number: 812780

Author: Jesús Manuel Antúnez Domínguez, PhD candidate

Contact: Partnership[at]microfluidic.fr

References

- C. E. Stanley, G. Grossmann, X. CasadevallI Solvas, and A. J. DeMello, “Soil-on-a-Chip: Microfluidic platforms for environmental organismal studies,” Lab Chip, vol. 16, no. 2, pp. 228–241, 2016.

- K. Aleklett, E. T. Kiers, P. Ohlsson, T. S. Shimizu, V. E. Caldas, and E. C. Hammer, “Build your own soil: Exploring microfluidics to create microbial habitat structures,” ISME J., vol. 12, no. 2, pp. 312–319, 2018.

- R. L. Wilpiszeski et al., “Soil Aggregate Microbial Communities: Towards Understanding Microbiome Interactions at Biologically Relevant Scales,” Appl. Environ. Microbiol., vol. 85, no. 14, pp. 1–18, 2019.

- S. Makarchuk, V. C. Braz, N. A. M. Araújo, L. Ciric, and G. Volpe, “Enhanced propagation of motile bacteria on surfaces due to forward scattering,” Nat. Commun., vol. 10, no. 1, 2019.

- M. Wu, F. Xiao, R. M. Johnson-Paben, S. T. Retterer, X. Yin, and K. B. Neeves, “Single- and two-phase flow in microfluidic porous media analogs based on Voronoi tessellation,” Lab Chip, vol. 12, no. 2, pp. 253–261, 2012.

- J. Deng et al., “Synergistic effects of soil microstructure and bacterial EPS on drying rate in emulated soil micromodels,” Soil Biol. Biochem., vol. 83, no. December, pp. 116–124, 2015.

- X. Wang, Z. Liu, and Y. Pang, “Concentration gradient generation methods based on microfluidic systems,” RSC Adv., vol. 7, no. 48, pp. 29966–29984, 2017.

- M. Whiteley, S. P. Diggle, E. P. Greenberg, and E. O. Wilson, “Bacterial quorum sensing: the progress and promise of an emerging research area Main text Humans have provided descriptions of the natural history of animals for millennia. Apart from basic anatomy and physiology, it was also noted that a number of animal,” Nature, vol. 551, no. 7680, pp. 313–320, 2017.

- D. Nichols et al., “Use of ichip for high-throughput in situ cultivation of “uncultivable microbial species,” Appl. Environ. Microbiol., vol. 76, no. 8, pp. 2445–2450, 2010.

- A. Burmeister et al., “A microfluidic co-cultivation platform to investigate microbial interactions at defined microenvironments,” Lab Chip, vol. 19, no. 1, pp. 98–110, 2019.

- H. Massalha, E. Korenblum, S. Malitsky, O. H. Shapiro, and A. Aharoni, “Live imaging of root-bacteria interactions in a microfluidics setup,” Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A., vol. 114, no. 17, pp. 4549–4554, 2017.

- A. Parashar and S. Pandey, “Plant-in-chip: Microfluidic system for studying root growth and pathogenic interactions in Arabidopsis,” Appl. Phys. Lett., vol. 98, no. 26, pp. 1–4, 2011.

- L. Boitard, D. Cottinet, N. Bremond, J. Baudry, and J. Bibette, “Growing microbes in millifluidic droplets,” Eng. Life Sci., vol. 15, no. 3, pp. 318–326, 2015.

- J. Park, A. Kerner, M. A. Burns, and X. N. Lin, “Microdroplet-enabled highly parallel co-cultivation of microbial communities,” PLoS One, vol. 6, no. 2, 2011.

- S. Hong, Q. Pan, and L. P. Lee, “Single-cell level co-culture platform for intercellular communication,” Integr. Biol., vol. 4, no. 4, pp. 374–380, 2012.

- S. G. Hays, W. G. Patrick, M. Ziesack, N. Oxman, and P. A. Silver, “Better together: Engineering and application of microbial symbioses,” Curr. Opin. Biotechnol., vol. 36, pp. 40–49, 2015.

- V. Kumar, M. Kumar, and R. Prasad, “Microbial action on hydrocarbons,” Microb. Action Hydrocarb., no. January 2018, pp. 1–667, 2019.

- A. A. Burghal, N. M. J. A. Abu-Mejdad, and W. H. Al-Tamimi, “Mycodegradation of Crude Oil by Fungal Species Isolated from Petroleum Contaminated Soil,” Int. J. Innov. Res. Sci. Mon. Peer Rev. Journal), vol. 5, no. 2, pp. 1517–1524, 2016.

- S. J. Edwards and B. V. Kjellerup, “Applications of biofilms in bioremediation and biotransformation of persistent organic pollutants, pharmaceuticals / personal care products, and heavy metals,” Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol., vol. 97, no. 23, pp. 9909–9921, 2013.

- B. Antizar-Ladislao, “Bioremediation: Working with bacteria,” Elements, vol. 6, no. 6, pp. 389–394, 2010.

- J. Kim, H. D. Park, and S. Chung, “Microfluidic approaches to bacterial biofilm formation,” Molecules, vol. 17, no. 8, pp. 9818–9834, 2012.

- Y. Yawata, J. Nguyen, R. Stocker, and R. Rusconi, “Microfluidic studies of biofilm formation in dynamic environments,” J. Bacteriol., vol. 198, no. 19, pp. 2589–2595, 2016.

- P. Cai et al., “Soil biofilms: microbial interactions, challenges, and advanced techniques for ex-situ characterization,” Soil Ecol. Lett., vol. 1, no. 3–4, pp. 85–93, 2019.

- E. J. Stewart, “Growing unculturable bacteria,” J. Bacteriol., vol. 194, no. 16, pp. 4151–4160, 2012.

Check the other Reviews

FAQ - Soil-on-chip: a review

1) What is soil-on-chip and why is it mandatory?

Soil-on-chip The microfluidic systems that are used to model and research soil systems on the microscale. Soil is a complicated environment in which there are minerals, water, gases, organic substances, microorganisms, fungal hyphae, and plant roots that are linked in heterogenous but balanced forms. The conventional soil research techniques fundamentally change the properties of soils in the analysis process, and none of the past models was able to reproduce and manage the effects of the spatiotemporal variation required to provide credible environmental simulation. Microfluidic systems provide the answer in terms of the correct matching of scales, low consumption of reagents, imaging through transparency, and a specifically targeted approach.

2) What is the mechanism of reproduction of physical heterogeneity in soil-on-chip systems?

Physical heterogeneity of soil involves barriers and obstacles which have an inhibitory effect on free circulation of substances and microorganisms. This is recreated using microfluidic tools with complex pillars and walls of channels with different shapes and sizes. The productive use of microfabrication, such as soft lithography and castings in PDMS, allows the customization to real soil types, depending on the real-world samples. The methods used are generated pattern of particles of different geometries, intersections of Voronoi Tessellation channels, and direct replication of pore structure. Such structures enable the examination of transport phenomena and active matter behavior and are also reproducible.

3) How do chemical heterogeneity in soil-on-chip devices come about?

Soil structure is a constant process which depends on gradients and movements of biological resources such as water, nitrogen, carbon dioxide one plus oxygen. Microfluidic systems recreate these gradients in a number of ways such as agar blocks and hydrogels in controlled release but these make them more opaque. More advanced designs involve the use of tree shaped channel flows, pressure balance systems and membranes to generate accurate concentration gradients. The methods help the researcher to model dynamic nutrient availability and investigate how organisms respond to the changing chemical environment.

4) What is the biological heterogeneity in soil microfluidics?

Biological heterogeneity deals with intricate associations among bacteria, fungi, plants and nematodes in soil. Soil-on-chip systems offer co-cultivation in a variety of ways as opposed to isolated cultures of single species. Isolation chips are chambers that isolate individual cells or populations in permeable chambers where they share common medium and products with other species without necessarily being in contact. In membrane-separated designs, evidence-based designs have different species circulated in parallel channels separated by permeable allowances. Such techniques assist in the interpretation of synergistic metabolism and quorum sensing that is naturally present in soil ecosystems.

5) How can the direct interactions in soil-on-chip be studied?

The microfluidic droplets used in the study of direct interaction between soil organisms are droplets in which each droplet is a complete isolated environment. Various developmental stages are experienced depending on the elements of the elements respectively in established interactions and relationships. This method is best in identifying symbiotic associations in which proliferation can be only achieved by direct contact with the species. The benefits of droplet format are parallel experiments, sorting by outcomes, and simplified screening. Alternatively, single-cell trapping is a method of isolated analysis of interactions without the complexity of droplet manipulation.

6) What are some of the ways through which the soil-on-chip platforms can help in bioremediation research?

Bioremediation involves the use of microorganisms to break down the harmful elements present in contaminated soil. A large number of soil bacteria and fungi have the ability to biodegrade hazardous substances such as crude oil, pesticides, and heavy metals. Nevertheless, natural systems can hardly offer the best conditions in terms of species occurrences, level of population, accessibility to pollutants, and availability of resources. The remediation processes can be optimized by use of SOC platforms that provide controlled environments where all the important parameters can be manipulated. By intervening, scientists can find appropriate species, define the best conditions to work in and work out strategies, but prior to the field process, which makes intervention more efficient and environmentally friendly.

7) What are the applications of biofilms in soil-on-chip applications?

Biofilms are supracellular formations in which microbial communities entrap themselves in the extracellular polymeric substrates. The collective behavior of biofilm is quite different compared to the behavior of free-moving cells, and it influences production of substances and survival needs. Multi-species biofilms mutually shield against environmental fluctuations as well as enhance the viability of the whole community. In comparison to microfluidic biofilm formation of aquatic and marine bacteria, soil biofilm studies with microfluidics are not that old. Knowledge of biofilm formation processes would facilitate the culturing of hitherto intractable soil taxa with bioremediation and pharmaceutical compound drug development applications.

8) What are the primary drawbacks of the existing soil-on-chip technology?

Regardless of significant progress, the majority of soil-on-chip studies have been done recently, and appropriate field development is yet to be discovered. The diversity of soil implies that there is no one device which can safely attempt to reproduce every characteristic of soil. The existing systems are oriented towards particular elements of the complex environment instead of full simulation. Other factors such as low supply of commercial soil-on-chip devices also act as a barrier to progress preventing access to a wider research community. Standardized and easy to access platforms should be created because such a move would greatly help the field by availing the required apparatus to more researchers.

9) What are the mechanisms of integrating plant roots and larger organisms in the soil-on-chip systems?

Enhanced soil-on-chip systems include more intricate organisms than microbes. The use of plant-root chips allows real-time imaging of the interactions of roots and bacteria under controlled conditions, the nutrient uptake, pathogen resistance, and symbiotic interactions. Integration of nematodes enables the study of predator prey interactions and movement of organisms using heterogeneous environments. Such multi-kingdom platforms are more realistic in terms of their ecosystem models, but more design complex. The integration is normally done with larger chambers or certain compartments which are attached to the main microfluidic network but provides environmental control.

10) What is the future of the soil-on-chip technology?

Future uses include identification of new pharmaceutical drugs using previously unculturable microorganisms of the soil, improving agricultural systems by learning about interactions between plants and microbes, coming up with sustainable bioremediation measures to practical contaminated sites, and screening useful microorganisms to improve crops. With the growth of devices in use and design options further developed, soil-on-chip platforms can allow the use of personalized soil management advice, quick analysis of soil health, and identification of microbial solutions to climate change mitigation via carbon sequestration. The technology is the interface between basic research and practice in agriculture, environmental management and biotechnology.