Unidirectional flow recirculation using an automated system vs peristaltic pump

Author

Celeste Chidiac, PhD

Publication Date

Keywords

unidirectional flow recirculation

Automated system

peristaltic pump

Cell culture pump & check valves

Need advice for your recirculation system?

Your microfluidic SME partner for Horizon Europe

We take care of microfluidic engineering, work on valorization and optimize the proposal with you

Recirculation with microfluidics

With microfluidics, it is possible to flow medium continuously over cells in culture. Microfluidic recirculation involves fluid’s continuous and controlled circulation through microchannels in a closed-loop or open system.

This system can be employed in spheroid cell culture, stem cell culture, organ-on-a-chip studies, for disease modeling and drug testing, since every cell of the human body is continuously irrigated via body fluids, whether in an open circuit (saliva, gastric fluid, urine…) or a closed circuit (blood, lymph, pleural fluid…) (Figure 1).

In addition, a microfluidic recirculation system efficiently eliminates waste, saves the culture medium, and enriches the medium with cell secretion factors.

Unidirectional flow recirculation

Unidirectional recirculation is preferred over bidirectional recirculation in applications like cell culture, biochemical assays, drug delivery studies, and organ-on-a-chip. In a unidirectional flow recirculation, the risk of backflow and contamination is minimized, and fluid mixing is improved without the turbulent interactions that occur in bidirectional systems, leading to more stable reactions.

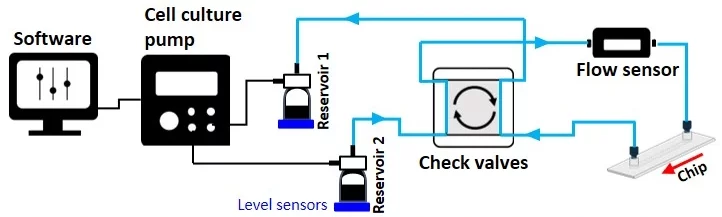

At the Microfluidics Innovation Center, we have developed an automated unidirectional recirculation pack that combines the check valves, the cell culture pump, and the level sensors.

In this review, we first compare our recirculation pack to unidirectional flow recirculation with a peristaltic pump. Then, we explain the story behind its development.

Comparison between recirculation with peristaltic pump and the automated recirculation system

| Recirculation system with peristaltic pump | Automated recirculation | |

| Common characteristics | Unidirectional flow | |

| Reduced reagent quantity | ||

| Volume-based | ||

| Different characteristics | Might need a CO2 incubator | No need for a CO2 incubator, might need a stage-top incubator |

| Less stable and accurate flow control | Highly stable and accurate flow control | |

| Pulsatile flow | Variety of flows: pulsatile, steady flow, stepwise…. | |

| Based on tube compression | Based on gas pressure | |

| Risk of recirculating cells damage | No risk of recirculating cells damage | |

| Tight-closed loop with 1 reservoir | Open loop with 2 reservoirs and check valves | |

| Input and output from the same reservoir | Automatic switch between reservoirs | |

Unidirectional flow recirculation with peristaltic pump

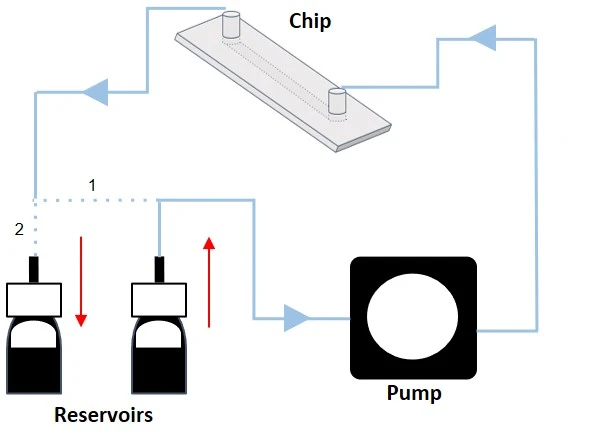

Recirculation with a peristaltic pump provides a physiologically relevant cell microenvironment by sustaining a unidirectional flow through a microfluidic chip laden with cells. Compared to single-pass systems, it also reduces the amount of needed reagents.

A peristaltic pump might need a CO2 incubator. It is a volumetric pump that compresses a flexible tube to transfer liquids, providing a pulsatile flow due to the cyclic nature of the peristaltic motion. Thus, the system can offer precise control but is less stable over time, requiring repeated flow rate calibration. Furthermore, due to the tube compression, there is a high risk of cell damage.

The system is volume-based and constitutes a tight-closed loop with only one reservoir serving as the input and output source (Figure 2).

Automated unidirectional flow recirculation

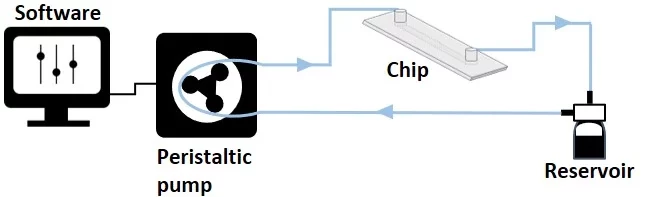

Our automated recirculation pack, which includes a cell culture pump and level sensors, offers the advantages of a pressure-driven flow controller plus the advantages of a peristaltic pump.

Similarly to recirculation with a peristaltic pump, our recirculation pack allows a physiologically relevant cell microenvironment by sustaining a constant unidirectional flow and reduces reagent quantity.

The cell culture pump is a pressure-driven flow controller that does not need a CO2 incubator. It offers a smooth, continuous, high-precision flow and the possibility of working with different flow profiles (pulsatile, steady, stepwise, etc.) based on the application. In addition, the pump is based on gas pressure with no risk of cell damage.

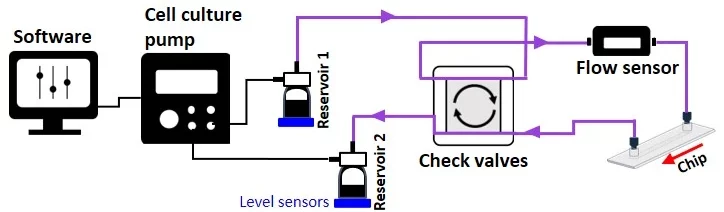

Moreover, the system is volume-based but constitutes an open loop of two reservoirs that can serve as input and output sources. The level sensor senses the sample volume inside the reservoirs, and the system automatically switches to the second reservoir when the first reaches the level sensor threshold (Figures 3-4).

From reservoir 1 to reservoir 2:

From reservoir 2 to reservoir 1:

We recently published a review comparing different bidirectional and unidirectional recirculation systems: hydrostatic pressure, syringe pump, peristaltic pump, and various setups with a pressure pump and active or passive valves.

The story behind it

Recirculation with a pressure-driven flow controller leads to a bidirectional flow inside the chip. However, an unidirectional flow is needed for cell culture, biochemical assays, drug delivery studies, and organ-on-a-chip models.

In addition, a closed circulation requires the medium to be supplied with CO2 inside the chip. Thus, a recirculation setup (with a pressure-driven flow controller or a peristaltic pump) using a gas-impermeable material and a CO2-dependent medium will need a CO2 incubator.

Moreover, recirculation with a pressure-driven flow controller is time-based. It relies on the initial fluid volume and desired flow rates to estimate the time it takes for one reservoir to flow most of its volume through the sample and then manually switch to the other reservoir. In addition, this system cannot detect changes and adapt its functioning accordingly. If one of the reservoirs empties before expected due to biofouling or clogging, it introduces air into the system and damages the cells, ruining the experiment.

To overcome these downsides, we integrated check valves, cell culture pump, and level sensors into the recirculation pack.

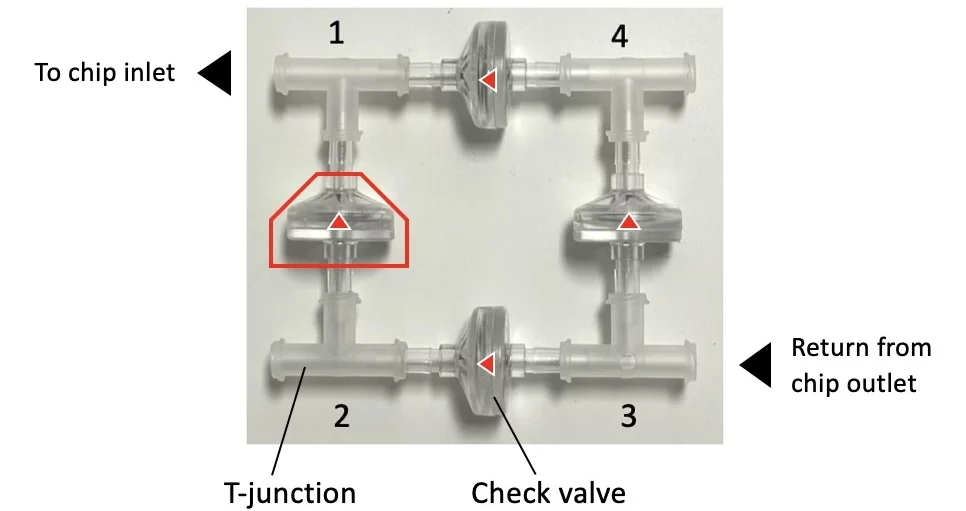

The check valve recirculation bridge (Figure 5) keeps the flow unidirectional inside the connected microfluidic chip via four passive valves that are adjusted to quickly and efficiently transfer fluid between reservoirs.

Check this video and this application note for more information on how to assemble the recirculation bridge and set up your experiment.

The cell culture pump is essential to the automated unidirectional recirculation setup. It maintains a stable and continuous nutrient supply at constant O2 and CO2 levels without needing a CO2 incubator (Figure 6). Then the setup might need an additional stage-top incubator to keep the temperature stable for long periods of time, allowing for high-quality live cell imaging experiments.

In addition, the cell culture pump does not exchange gas with the atmosphere as most pressure-driven controllers do. Pressuring the media reservoir with the correct gas mix prevents the gas in the media from diffusing into the atmospheric air. The constant media flow ensures that the correct composition always reaches the cells, even if the rest of the system is not gas-tight.

The system, including level sensors (Figure 7), is volume-based; it will pressurize the first reservoir until it is nearly empty, then stop and start pressurizing the second reservoir. The researcher doesn’t have to wait for the first reservoir to reach the level sensor threshold to switch to the second one.

Moreover, the level sensors introduce a fail-safe mechanism that considers the ever-evolving nature of a recirculation system, such as fouling of the tubing with dead cell debris, leakage due to clogging, and other blockage-related issues such as air entry.

Funding and Support

The LIFESAVER project, funded by the European Union’s H2020-LC-GD-2020-3, grant agreement No. 101036702 (LIFESAVER), helped develop the level sensors.

The Tumor-LN-oC project, funded by the European Union’s H2020-NMBP-TR-IND-2020 grant agreement No. 953234 (Tumor-LN-oC), helped develop the cell culture pump.

The ALTERNATIVE project, funded by the European Union’s H2020-LC-GD-2020-3 grant agreement No. 101037090, helped develop the check valve system.

The Galileo project, funded by the European Union’s Horizon research and innovation program under HORIZON-EIC-2022-TRANSITION-01 grant agreement No. 101113098 (GALILEO), helped develop the Galileo flow sensor.

This “quick tips” was written by Celeste Chidiac, PhD.

Published in July 2024.

Contact: Partnership[at]microfluidic.fr

Check more Quick Tips

FAQ - Unidirectional flow recirculation using an automated system vs peristaltic pump

1) What is “microfluidic recirculation” in cell culture?

Most of the time, fluid moves continuously through a chip, giving cells a steady flow rather than a one-through exposure. This movement might complete a full circle or mimic a loop, even without sealing shut. A main reason stands out clearly: supply fresh nutrients constantly while removing byproducts efficiently. Less liquid gets used overall because of this setup. Secretions from cells build up gradually under regulation, avoiding immediate dilution each time new solution arrives.

2) What makes one-way flow more common than two-way movement in recycling systems?

Flow that moves in two directions might seem easier to set up, yet it often clashes with biological needs or test accuracy. Moving fluid one way cuts down on backward leaks, along with the contamination issues they bring, while also supporting more stable testing environments – particularly in cell cultures, chemical tests, medication research, and microchip-based organ simulations. Simply put: less back-and-forth means fewer unexpected results.

3) How does one most easily contrast a peristaltic recirculation system with an automatic single-flow arrangement?

A single reservoir usually feeds a peristaltic pump setup, in which tubing is squeezed to push fluid through a narrow loop. Instead of squeezing, MIC’s method pushes liquid using air pressure between two separate tanks. One-way movement happens not from mechanical rollers, yet via small valves that block backward drift. Volume measurements guide operation here, unlike sensors tracking position or speed. Switching tanks occurs automatically, triggered when levels change enough to signal the transfer time. Flow direction stays fixed even though the structure runs openly, different from sealed setups tied back on themselves.

4) Could a peristaltic pump actually deliver cell environments close to real bodily conditions?

One reason it qualifies is that it keeps fluid moving steadily across cells within a chip, somewhat like living tissue in the body, unlike static cultures. Trouble emerges because the movement isn’t smooth – it pulses, thanks to the way peristaltic pumps work by squeezing repeatedly. That rhythm might not matter at times, or some may actually want it; however, when experiments run longer, those ripples introduce inconsistency, particularly if consistent force on cell surfaces matters.

5) Why do people say peristaltic pumps can be less stable over time? Don’t they have “precise control”?

Over days or weeks, repeated squeezing wears down the material. This changes how much fluid moves each cycle. Even if labeled as accurate at first, performance shifts gradually. So while initial settings seem exact, consistency fades later. Precision might hold early on – yet long-term reliability often drops. Some call them reliable, but in practice, they show otherwise under constant use.

Reality often reveals itself during extended operation, though initial settings might appear accurate; this happens because constant squeezing of the tube gradually shifts the output, requiring frequent recalibration. Peristaltic pumps aren’t flawed by design – rather, their performance ties closely to how flexible the tubing remains, how much it has aged, changes in heat, resistance in the line, and even minor misalignment during installation. Within microfluidic systems, tiny inconsistencies gain importance quickly.

6) Could cellular waste buildup pose a core issue when using peristaltic flow in lab-grown tissue systems?

The piece clearly states that pressure shifts within tubes, along with rhythmic flow patterns, often lead to serious harm to cells when fluid cycles back. Working with sensitive cultures, tightly bound cellular sheets, or complex three-dimensional arrangements? Mechanical strain and uneven current might override biological limits. Instead of physiology, physics takes control.

7) What does MIC’s “automated unidirectional recirculation pack” actually include?

Check valves, paired with a pressure-controlled cell culture pump, form part of this setup. Flow moves steadily in one direction thanks to their coordination. Level sensors monitor liquid height throughout operation. Should blockages occur or fluid levels shift without warning, adjustments happen automatically. Less reagent is used because the delivery stays precise. Safety improves since responses follow deviations instantly. Clogs, leaks, buildup, or sudden volume drops trigger feedback loops. The design handles these shifts without outside help.

8) What keeps the movement one-way in an automated setup when pressure drives the pump?

Pulling liquid through the system often results in back-and-forth movement within the device. To fix this, a special bypass with one-way gates ensures motion stays unidirectional. These small valves act like traffic controllers, opening and closing in response to pressure changes. Flow keeps moving forward, regardless of which chamber drives it at any moment. Direction depends entirely on how these channels are arranged. What emerges is a network that behaves predictably without active switches.

9) What problem do level sensors solve in real experiments (beyond “automation for convenience”)?

Fail-safes often come into play here. Instead of relying on timed switches – where someone guesses when a reservoir runs out and changes it by hand – there’s a better way, since real-world behavior seldom follows theory. Things like gunk buildup, tiny blockages, leaks, stray particles, or accidental air intake shift how fluid moves, sometimes draining tanks sooner than expected. An unintended dry-out risks pumping air into sensitive areas, harming living cells and ending trials prematurely. Sensors that track liquid levels step in at key points, triggering swaps without help. This kind of setup handles unpredictable conditions far more reliably.

10) Still wondering about needing a CO₂ incubator when using such systems? Then there’s the question: what do you give up with a stage-top design instead?

Depending on the materials and media used, needs can vary. When systems rely on gas-impermeable components along with CO₂-sensitive media, a standard CO₂ incubator is often necessary, according to the article. However, the MIC cell culture pump operates without such an incubator. Instead, automation might pair with a stage-top unit – this keeps temperature steady during extended runs while supporting clear live-cell imaging. So, reliance on traditional incubation drops; yet heat regulation moves nearer to the imaging setup.

11) How does the cell culture pump method differ when it comes to handling gases and adjusting fluid makeup?

It might seem minor, yet it matters: the media reservoir is pressurized with a precise blend of gases. This prevents dissolved gases in the liquid from escaping into the surrounding air. Because fresh media keeps moving through, oxygen and carbon dioxide levels stay steady at the cell level. Even small leaks elsewhere matter less when this setup works right. In extended organ-on-chip experiments lasting days, stability like that shifts outcomes – three hours of viability versus three full days without decline.