Mechanically tuned lung-on-a-chip model: MECH-LoC

Author

Lisa Muiznieks, PhD

Publication Date

October 14, 2018

Status

Keywords

air–liquid interface membrane chip

Lung‑on‑a‑chip

mechanical strain

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease

alveolar-capillary barrier

pulmonary disease modelling

Your microfluidic SME partner for Horizon Europe

We take care of microfluidic engineering, work on valorization and optimize the proposal with you

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) affects about 10% of the population, reducing the quality of life of affected patients.

Lung-on-a-chip models may help to tackle these diseases and propose new treatments.

Mechanically tuned lung-on-a-chip device: introduction

To better understand chronic obstructive pulmonary diseases, like emphysema or chronic bronchitis, and to screen potentially efficient drugs, appropriate lung models must be developed.

Based on 2D cell culture or living animal studies, the current models are pretty limited in physiological relevance.

Advances in microfluidics, particularly organ-on-chip, offer a powerful alternative to studying the lung membrane, providing a more realistic 3D cell culture environment and the potential to reduce the number of animal studies.

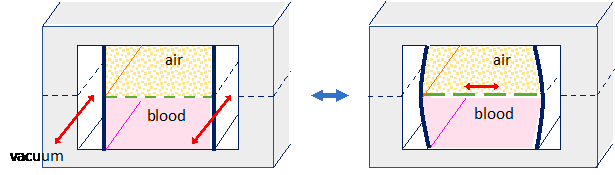

State-of-the-art lung-on-chip systems model the lung using two chambers, one filled with air and the other with liquid, separated by a semi-permeable membrane, typically a thin layer of flexible polymer such as polydimethylsiloxane (PDMS).

Cells are seeded on each side of this membrane to reproduce the liquid/air interface. Flanking vacuum chambers allow the membrane to be cyclically inflated to replicate breathing. This lung-on-chip system is suitable for measuring gas exchange, metabolite concentrations, or screening new drugs.

Mechanically tuned lung-on-a-chip device: our role

Lungs are constantly undergoing mechanical stress during breathing, making the elasticity of the membrane a crucial parameter for understanding lung diseases.

However, the polymer typically used to mimic the air / liquid membrane has an elastic modulus of up to one thousand times higher than its physiological equivalent and does not offer biological stimuli.

To advance lung-on-a-chip models, this project aims to control the membrane’s mechanical properties by adding fibrous matrix proteins (e.g., collagen and elastin). The fast and stable microfluidic flow control system will help to finely control membrane deformation and culture media.

The mechanical properties of this model lung membrane can be thus adapted to different disease phenotypes to be as relevant as possible in the development and screening of treatments.

As an alternative to conventional organ-on-a-chip materials such as PDMS, we also intend to use FlexdymTM, a polymer, to make our lung-on-a-chip devices. This fully biocompatible material makes the integration of cells into the system possible before chip assembly.

Mechanically tuned lung-on-a-chip device: results

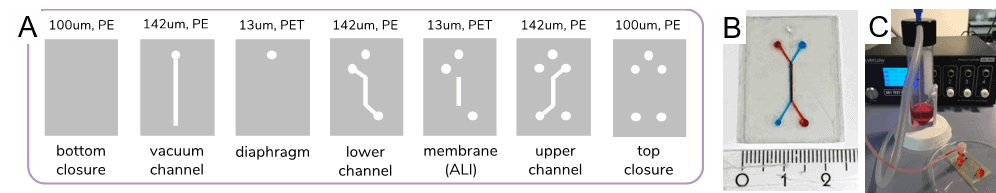

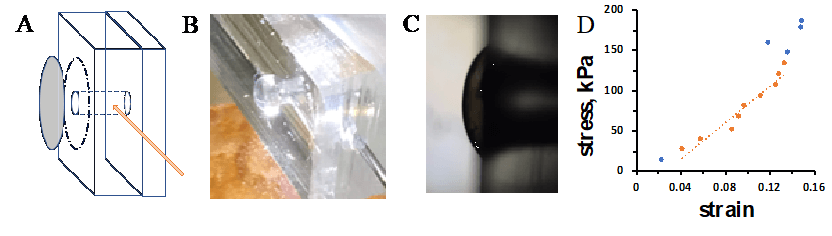

1. Perfusable lung-on-chip assembly

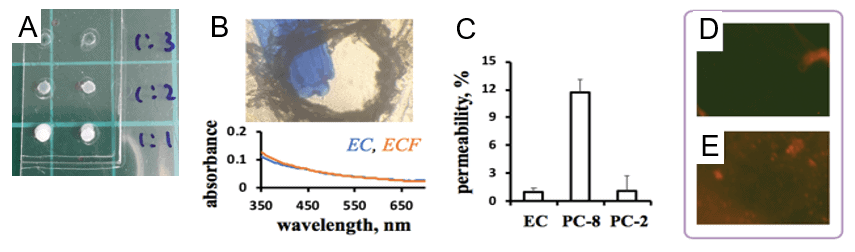

2. Protein membrane physical characterization

3. Protein membrane mechanical characterization

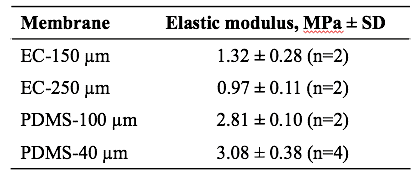

Table 1. Elastic modulus values for protein membranes (elastin-collagen, EC 1:1) compared to PDMS spin coated films. Membrane thicknesses are indicated.

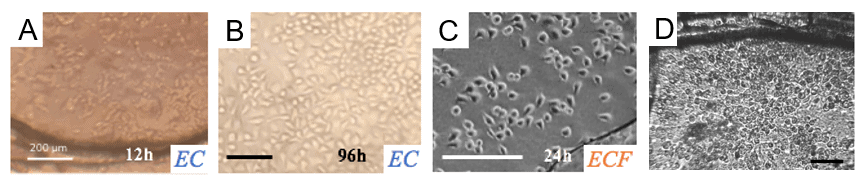

4. Characterization of protein membrane biocompatibility

Mechanically tuned lung-on-a-chip device: conclusion and perspective

Protein membranes’ sustained integrity and mechanical tunability illustrate their suitability as cell substrates for barrier models in perfusable microfluidic devices.

These studies reveal substantial opportunities to tailor membrane biomechanical activity to match physiological cell environments more closely and suggest the potential to define OOC devices with physiological and disease-matched mechanical profiles.

Read here the CORDIS interview with Dr. Lisa Muiznieks on her project at the Microfluidics Innovation Center, her goals, and her plans!

Related content

If you want to learn more about modeling the air-liquid interface in lung-on-a-chip applications, read this review.

Funding

This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Sklodowska-Curie grant agreement No 793749 (MECH-LoC).

Researcher

Dr. Lisa Muiznieks

Research Associate

- Post-Doc at Hospital for Sick Children (Canada), working on elastin structure and function

- PhD in Biochemistry (Sydney University, Australia)

- Bachelor of Science in Molecular Biology and Genetics (Sydney University, Australia)

Areas of expertise:

Structural biology, Protein elasticity, Lung-on-a-chip, Air-liquid interface.

Check our Projects

FAQ – Mechanically tuned lung-on-a-chip model: MECH-LoC

What is Mech-LOC in one sentence?

A lung-on-a-chip system that is modular, allowing you to dial in the mechanics – cyclic stretch, airflow, and substrate stiffness to recreate a healthy and disease pulmonary microenvironment using primary human cells at the air-liquid interface.

What is the rationale behind such insistence on the use of a mechanically tuned instead of a standard airway chip?

Since the mechanisms of lung physiology are mechanical, the alveolar barrier undergoes strain with every breath, airflow, perfusion shear, and disease-associated matrix stiffening. These cues act on cell behavior by orders of magnitude more than most soluble factors. During fibrosis, e.g., matrix stiffness normally increases in the range of soft-kPa (physiologic) to tens of kPa; there is a corresponding change of phenotype in epithelial and fibroblast. Mech-LOC allows you to configure those parameters independently, rather than accepting a fixed chip configuration.

What knobs are possible to turn?

There are three categories of controls constructed:

- Repeated strain of an elastic, microporous membrane (typically 5-15% peak-to-peak; frequency values range between “resting” c. 0.2-0.3 Hz to c. 1 Hz when using membranes to test the stress resistance of the material).

- Flow and shear on both apical (air or aerosol) and basal (microvascular perfusion) surfaces at a resolution of mL-mL/min.

- Substrate stiffness, with interchangeable membranes or surface treatments, to mimic soft parenchyma and fibrotic tissue. In practice, most users combine moderate strain with a stiffer substrate to simulate early fibrotic remodeling.

Is it possible to model particular pathologies - COPD, asthma, ARDS, fibrosis?

Yes. Three common patterns:

- COPD/asthma: decreased oscillatory strain, modulated apical shear, mucin dynamics; supplement episodic, spasmogenic occurring obstacles.

- ARDS/ventilator injury: high-strain or high-rate regimens to simulate overdistension; barrier leak is measurable; cytokine storm is measurable.

- Fibrosis: stiffer substrate (≥10 kPa equivalent) containing TGF-β signals; monitor EMT indicators, collagen deposition, and changes in mechanotransduction.

What about throughput and reproducibility?

The standard run can process 12-24 separate chips (plate-compatible manifolds). Using pre-qualified membranes and SOPs, user-to-user variability generally decreases to less than the biological variability of primary donors. When mechanics are a variable, we suggest 3-5 donors to achieve strong conclusions.

What's inside the hardware?

The vacuum-actuated side chambers provide cyclic stretch to a thin, optically clear, microporous elastomer membrane. The airflow and perfusion are orthogonally controlled by microfluidic channels above/below the membrane. Software-controlled pressure, flow, and vacuum, standard logging. TEER, oxygen-sensing, and stepwise-protocol optional modules are added to the on-chip valve.

Validation- what has been demonstrated on Mech-LOC actually?

Mechanical tuning previously recapitulated the anticipated patterns in barrier permeability and inflammatory signaling, such as stretch-sensitive increases in IL-6/IL-8 and cytoskeletal restructuring, and maintenance of the epithelial tight junctions across physiologic strain ranges. The rank order of shifts with 4- and 70-kDa tracers is identical to that reported in the literature on lung-on-chip.

What is the comparison with animal models or the case of cost/time of static inserts?

The set-up costs are front-loaded (controller + manifold + chips); however, the per-condition cost is sharply low since multi-factor designs (strain x stiffness x dose) can be run within the same week. The time-to-signal is reduced: it can take a few hours (24-72h) to get many mechanical phenotypes, whereas animal fibrosis models can require weeks. And you leave human-of-interest dosing to the barrier of your actual concern.

What would be the TRL and approach model today?

We take into account the platform at TRL 5-6: an integrated prototype with validated working processes and already deployed in collaborative projects. Some of the access options will be fee-for-service studies, co-development (shared IP when needed), or inclusion in Horizon Europe work packages.

I am developing a Horizon Europe consortium- where should MIC be placed outside this project?

MIC is a microfluidics SME that regularly participates in EU consortia, providing hardware, automation, and measurement components for complex bioassays. We prepare offers together, model work packages based on prototype deliverables, and risk-proof manufacturable designs. Consortia incorporating MIC prototype-first model usually claim success rates that are twice the official baseline at similar calls, a trend due to technical feasibility, believable milestones, and early demonstrators.