Microfluidic phase-change cooling of microprocessors: ThermaSMART

Author

Christa Ivanova, PhD

Publication Date

December 14, 2017

Status

Keywords

phase-change cooling

two-phase flow

heat transfer

microprocessor cooling

bubble dynamics

electronics reliability

multiphase flow

Your microfluidic SME partner for Horizon Europe

We take care of microfluidic engineering, work on valorization and optimize the proposal with you

Phase-change cooling is one of the options for efficient thermal management of microprocessors. ThermaSMART aims to enhance the performance of these systems using microfluidics.

A performant microfluidic system for phase-change cooling: introduction

Microprocessors are the basis of all electronic devices, but constant cooling is necessary to maintain their speed durably.

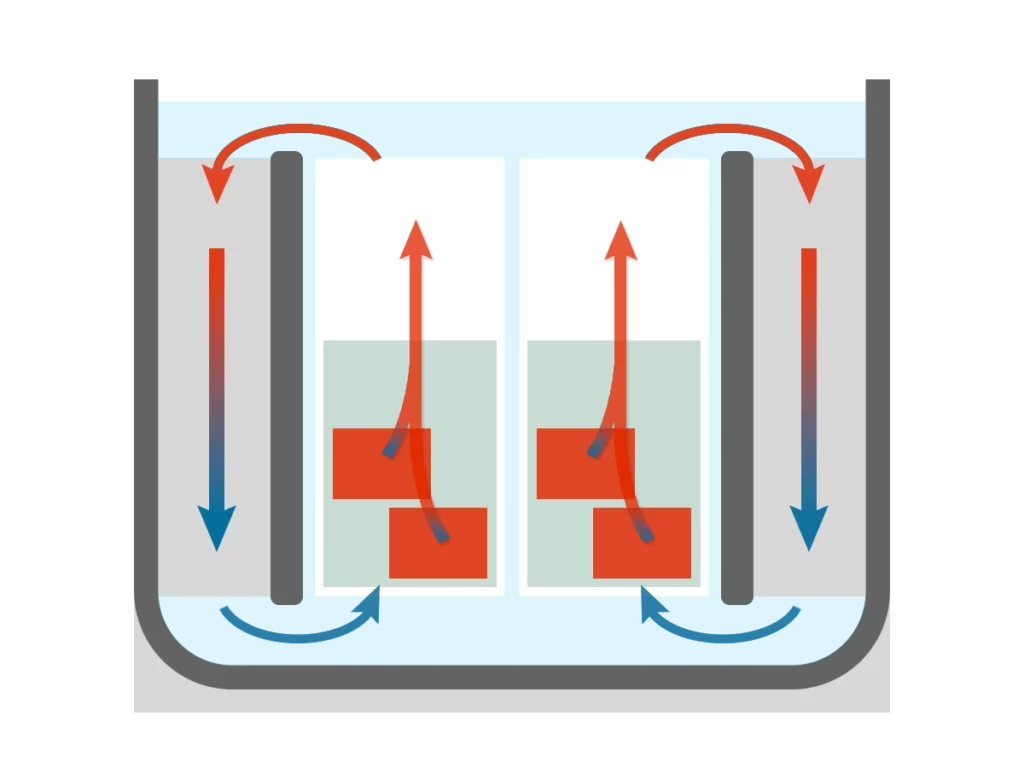

Microprocessor cooling can be achieved by using phase-change systems in which the condensation of a liquid leads to the production of cold. Ideally, the produced heat must be dissipated as fast as it was generated, but the current air-cooling systems are only 60% effective.

The complex flows in these systems are not yet fully understood and could be better optimized.

ThermaSMART consortium gathers partners from five continents (Europe, Asia, Africa, North America, and South America) who share their knowledge within this multidisciplinary network. The aim is to develop theoretical models and experimental methods to better understand phase-change cooling and design a new generation of cooling systems based on microchannels.

Phase-change cooling with microfluidics: project description

In the ThermaSMART project, we will transfer knowledge on microfluidics instrumentation, flow control, and innovation to the other members of the consortium in the frame of workshops and training.

Based on the fast and precise OB1 flow controller (Elveflow), our expert handling can be leveraged to design the cooling microdevice.

The Cherry Biotech company, also participating in this consortium, will share its experience in temperature control in microfluidic devices to develop an evaporator in microchannels as a central brick for this new generation of phase-change cooling systems.

This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 MSCA-RISE under grant agreement No 778104 (ThermaSMART project).

Check our Projects

FAQ – Microfluidic phase-change cooling of microprocessors: ThermaSMART

What is indeed the problem that ThermaSMART is addressing?

The concentration of heat in small hotspots by modern CPUs and power electronics is the area where traditional single-phase liquid cooling or air cooling fails. ThermaSMART considers two-phase, microfluidic strategies, boiling and condensation in engineered microchannels, to draw heat at its sources with minimal pressure drops and minimal pumping power.

Why not simply force more liquid through a cold plate by pushing it through, rather than boiling it?

A change of phase in a fluid transfers on average a vast amount of energy per unit mass (latent heat) than can be worked by sensible-heat convection. Practically, this implies increased heat-flux management in a smaller area, and with the hydraulics correctly designed, will result in improved coefficient of performance of the entire cooling loop.

What is a microfluidic heat sink here?

Imagine a plate under the chip made out of thin silicon (or copper) of labyrinthic micro- to milli-scale channels. Some incorporate capillary structures or micropillars to facilitate evaporation of thin-film; those that are manifolds that evenly distribute flow so that you do not choke one hot spot and flood another.

What is the place of MIC in ThermaSMART?

MIC provided the fluidic architecture and the engineering glue: fixed microchannel formats, flow-distribution logic, and start-up transient test protocols, oscillatory boiling test protocols, and dry-out recovery test protocols. We also worked on designs which could be made, bonding options, antifouling coatings, and those interfaces which would interface with conventional packaging.

What type of thermal performance do we have?

Depends on the coolant and geometry but two-phase microchannel systems are typically aimed at sustained heat fluxes of the hundreds of W.cm⁻² on representative footprints with a junction-to-fluid thermal resistance reduced drastically compared to single phase plates. It is not to get to maximal values, but to operate steadily in cases of workloads drifting.

What is your method of preventing instabilities, chatter, flow reversal or local dry-out?

Three layers: (i) Manifolded distribution to smooth out maldistribution due to parallel channels; (ii) Capillary/porous characteristics allowing a thin liquid film to be pinned at the wall during nucleation; (iii) Control envelopes (inlet sub-cooling, back-pressure, ramp rates) which keep the system away the worst corners of the boiling map. We intentionally operate into those regimes in order to map operating safely.

Microfluidics overhead of pumps and parasitic power, is microfluidics an overhead?

Not necessarily. The pressure drops remain modest with the right manifolds and channel aspect ratios. Since latent heat is an efficient method of heat transport, it is possible to achieve the same amount of heat removal at a lower flow rate. The design objective is a system-level win: increasing the amount of watts cooled per watt transferred to the fluid.

How do you do it without only guesswork testing such a coupled (fluid + heat + mechanics) system?

These are used together with high-speed thermometry (IR or embedded sensors), pressure/flow logging and where necessary transparent test coupons can be used to visually monitor the flow regime. The metrics used to accept them are critical heat flux, uniformity of temperature across synthetic hotspots, recovery following power steps, and stability in the long run provided realistic traces of power.

What actually emerged from the project can actually be used by the partners?

A library of heat-sink designs that can be manufactured, a set of rules-of-thumb in manifold, start-up/shut-down SOPs; safe envelope information on popular coolants; interfaces to package the micro-heat-sinks with server-class cold loops would be needed. A number of modules were taken to demonstrators which can be modified to HPC, RF power, or edge-AI boards.

What would the working of collaboration with MIC under Horizon Europe look like?

We are generally the leaders in the microfluidic architecture, rapid prototyping, test/QA automation, and co-leaders in exploitation. Having a robust SME can be seen to increase the chances of a proposal by significant factors; in several European consortia, projects involving MIC have previously outperformed official success rates by factors of two or more. Early prototypes of heat-sinks are also provided by us, to establish milestones; reviewers like the physical risk reduction.