Microfluidic photochemistry: Phototrain

Author

Alexander Mc MILLAN, PhD

Publication Date

October 22, 2016

Status

Keywords

light‑fueled chemical processes

green synthesis

photochemical microreactor

microfluidic photochemistry

solar energy conversion

photoactive interfaces

Your microfluidic SME partner for Horizon Europe

We take care of microfluidic engineering, work on valorization and optimize the proposal with you

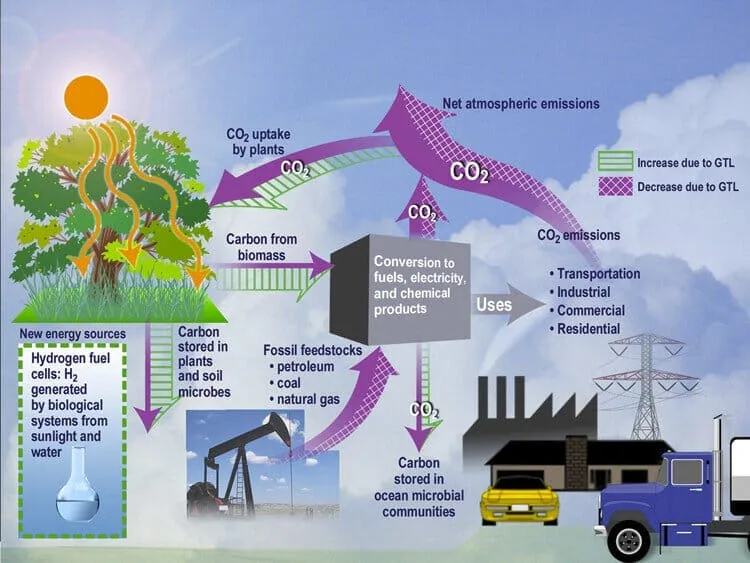

While there is currently a need to move human technologies into a sustainable future, eight European organizations from France, Italy, Spain, the UK, and Belgium and one institution from Israel will unite around the PHOTOTRAIN Project and study how photochemistry could lead us to this sustainability.

The main goal of the PHOTOTRAIN Project is to develop light-fuelled processes thanks to a microfluidic device.

A hope of sustainable solutions for the future: introduction

Today, light can provide valuable and sustainable alternatives to help us temper climate change and meet energy demands by providing energy and reducing energy consumption.

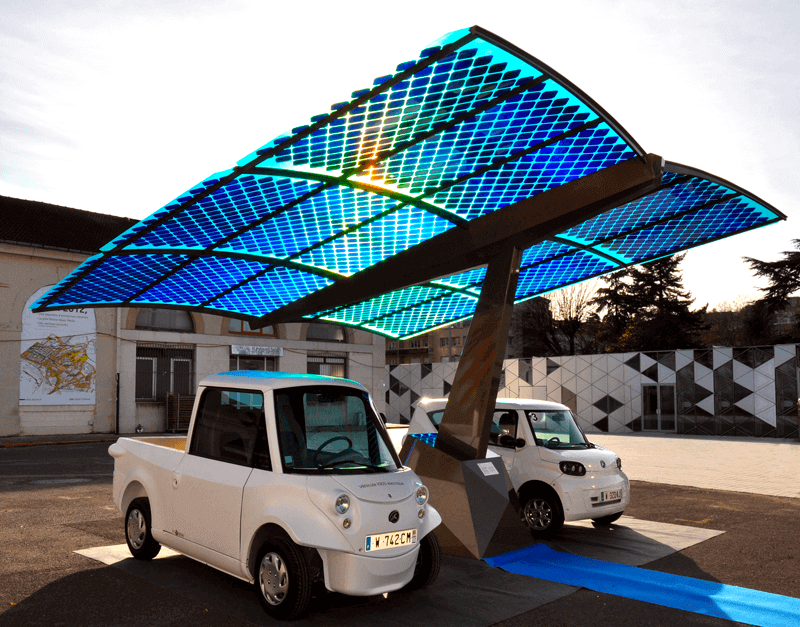

For instance, new materials are being developed to collect solar energy.

Furthermore, solar lighting (lamps that recharge during the day thanks to solar energy) has proved its efficiency in developing countries, giving a light source after nightfall to people who don’t have access to electricity.

Now, it is commonly admitted that the 21st century will depend as much on light energy as the 20th century depended on electronics. This is the reason why the PHOTOTRAIN Project focuses on photochemistry and its applications.

Photochemistry and microfluidics: project description

The main goal of the Phototrain project is to transform light-fuelled processes from a proof-of-principle to an exploitable process. To achieve this goal, they will use fundamental concepts in supramolecular chemistry and photochemistry to build functional photoactive interfaces that can be implemented to produce scalable and sustainable quantities of products.

Indeed, they will have to discover and implement new principles in photoinduced energy transfer and charge separation to enable the development of exploitable catalytic technologies based on versatile, robust, and low-cost microfluidic devices.

We hope this project will help us make our way to a sustainable future where photochemistry enables us to use light as a fuel in multiple and different areas.

This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme under the Marie Sklodowska-Curie grant agreement No 722591 (PhotoTrain project)

Researcher

Alexander Mc MILLAN, PhD

- Division Business Manager – Darwin Microfluidics

- Master of Engineering – Mechanical & Electrical Engineering, Edinburgh (Scotland)

Areas of expertise:

Data analysis, Microfluidics, Computer-Aided-Design (CAD)

Check our Projects

FAQ – Microfluidic photochemistry: Phototrain

What was PHOTOTRAIN in one sentence?

A network of trainings funded by the EU that set photochemistry out of the gilded bench science into scalable and microfluidic flow processes, and conditioned a new generation of young scientists to make photochemical manufacturing clean and fast.

What was the number of researchers that were trained, and what was training here anyway?

The network included 14 early-stage researchers (ESRs) who did local trainings, network-wide schools, laboratory secondment, and practical research in photochemical flow, catalysis, and microfluidics. In addition, each ESR achieved specific career development milestones.

What was the intended photochemistry issue that the project set out to address?

Classic batch photochemistry is plagued with attenuation of light, hot spots, and nonuniform dose; microfluidic flow reactors level out those gradients to provide short diffusion paths, high surface-to-volume ratio, and predictable residence times, just what you need when quantum-yield-limited steps and weak intermediates are involved. The numerous sources in the general literature and those of PHOTOTRAIN go to the same plank: selectivity is enhanced, and scale-up logic is enhanced by controlled illumination and continuous flow.

But then what about microfluidics, what is the concept of reactor?

Consider a shallow meandering flow next to a collimated source of light: photons observe a fixed path length, reagents observe laminar, well-defined residence time, and heat is swept away through the chip. The flow is driven by pressure to allow control of residence-time without pulse artifacts, and the swapping of path lengths or materials to match the wavelength and catalyst can also be undertaken using modular chips. This forms the basis of flow photochemistry rigs of MIC.

What was the actual contribution of MIC (the Microfluidics Innovation Center)?

Hardware and expertise: pressure-based controllers, microreactor chips with short optical lines, and workable SOPs to take the bench illumination to steady and continuous operation, including inline monitoring options for rapid optimization. It is a practical philosophy, plug-and-play, then repeat.

What are the quantifiable benefits that a lab can hope to receive by transferring a photoreaction to microfluidic flow?

Usually: (i) increased space-time yields of light-limited steps, (ii) greater selectivity, since all the molecules are exposed to the same photon flux, (iii) increased safety when handling reactive intermediates, and (iv) an easy numbering-up of channels; this is achieved by parallelizing channels instead of scaling up a single vessel. The results obtained exactly justify the reason why photochemical techniques are moving into flow, as training networks such as PHOTOTRAIN hoped.

How does the generally used experimental layout of MIC flow photochemistry pack look like?

A pump that operates on a calibrated pressure, a transparent meander microreactor (small depth to reduce light attenuation), an apparatus to hold a source of light directly in the channel, and rudimentary controls to initiate and stop the flow and adjust the residence time. It is meant to substitute ad-hoc tubing reactors and it shortens the time delays between idea and reliable kinetic data.

Why would we include an expert SME such as MIC in the construction of a Horizon Europe consortium on photochemical manufacturing?

This is because reviewers reward credible implementation. MIC ushers in microfabrication, flow engineering, and automation; we deliver prototypes with instrumentation and validation plans regularly that pass scrutiny from work-package reviewers. Even in recent bids, consortia such as MIC have, on average, doubled their chances of proposal success as compared to formal Horizon baselines, due to more robust approaches, risk tables, and realistic deliverables.

What will be our engagement - service or co-development or shared IP?

All three are possible. Frequently, the initial step involves a fee-based feasibility run (not months) by many teams followed by incorporation of MIC into the grant as a prototyping and validation partner. In the case of ambitious aspirations, it may be the quickest path to technology transfer to co-development with common IP and piloting demonstrator.

How do you find it common to trap yourself in the first attempt at transferring a photoreaction to microfluidic flow?

Two repeat mistakes: (a) too deep reactors (reactors that are too deep cause the flux of photons to die with depth), and (b) no account of catalyst wall-adsorption (this skews kinetics). We risk with superficial channels, material selection (quartz, COC, coated glass), and initial and cheap illumination mapping, then go all the way to full DoE campaigns.

And there is PHOTOTRAIN, then what?

The knowledge-based design standards and safe scale-up of industrial photochemistry are now being driven by Europe; MIC is fitting into those paths with microfluidic reactors, analytics, and automation to reduce the time between concept and pilot.