Soil-on-chip devices in the study of microbial communities: Active Matter

Author

Jesús Domínguez

Publication Date

September 14, 2019

Status

Keywords

microbial communities

Soil-on-chip

bioremediation

chemical gradients

heterogeneity in soil

microbiology

soil ecology

soil-microbe interactions

Your microfluidic SME partner for Horizon Europe

We take care of microfluidic engineering, work on valorization and optimize the proposal with you

Microfluidic soil-on-chip devices: introduction

Soil-on-chip devices will have many applications. Soil is a complex environment defined by a main characteristic: heterogeneity.

Soil-on-chip devices will have many applications. Soil is a complex environment defined by a main characteristic: heterogeneity.

The conditions of this system, such as topography and composition, are highly irregular and often prone to changes, leading to the development of diverse and interlinked microbial communities with a broad set of requirements for their survival.

Many of these requirements can be challenging to control artificially, namely the communication and interactions between microbial species. For that reason, even to this day, very few of the soil-dwelling microorganisms can be cultured in a laboratory and be adequately studied.

Since direct monitoring of actual soil samples often implies a fundamental alteration of the medium to the extent where the natural properties and original behavior are lost, the need arises for a device to recreate such conditions while allowing analysis.

Microfluidic soil-on-chip devices: project description

What is more, given that most of the microbes in the soil behave as active matter (composed of large numbers of active “agents,” each of which consumes energy to move or to exert mechanical forces), information about its movement and expansion through the available space depending on the set conditions can also be extracted. This offers valuable insight into environmental science, microbiology, and physics.

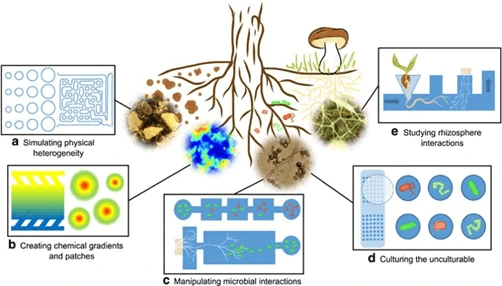

This project aims to overcome many obstacles in microbial monitoring through microfluidics, where some general advantages like transparency, the tailored shape of microfluidic chips, and the possibility of establishing chemical gradients are exciting.

As a result, many valuable applications can be derived from a better understanding of the soil system, including bioremediation, enhanced crop growth, and the development of new antibiotics. This is what soil-on-chip devices aim to achieve.

Related content & results from this project

In the light of the Active Matter project, we developed a microbiology incubator.

We also published a review about soil-on-chip devices, and another one about microswimmers chemotaxis behavior.

Funding

This soil-on-chip project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon research and innovation program under the Marie Sklodowska-Curie grant agreement No 812780 (ActiveMatter project).

Researcher

Jesús Domínguez

Marie-Curie PhD Candidate Elvesys/Gothenburg University

- Traineeship in Nanoparticle Characterisation (Joint Research Centre in Geel, Belgium)

- Double University Degree in Physics and Materials Engineering (Universidad de Sevilla, Spain)

Areas of expertise:

Physics, physical chemistry, materials science, rheology, chemical engineering, nanotechnology, particle characterisation, emulsions.

Check our Projects

FAQ – Soil-on-chip for the study of microbial communities: Active Matter

What is a soil-on-chip, and why would anybody build one?

It is a microfluidic hat that reconstructs the key processes of soil by its tortuous pores, steep chemical gradients as well as patchy structure inside a transparent chip. True soil is not clean and homogeneous; most soil organisms cannot grow in conventional laboratory cultures. A soil-on-chip is an instrument that helps scientists observe interactions and motility in a controlled, realistic environment that is important.

What does the Active Matter perspective lead to in changing the way we research soil microbes?

The actions of many soil microbes are active: they dissipate energy to move, push, and restructure their microenvironment together. Active matter offers the opportunity to ask quantitative questions, such as the nature of front propagation, clustering, etc., which are difficult to address with bulk assays. Microfluidics implements the missing element: meticulously designed sceneries on which such dynamics may be quantified, one frame at a time.

What are the scientific issues that would be best addressed on a soil-on-chip platform?

There are three that are revisited over and over again: (i) communication and competition between microbes in confined geometries, (ii) chemotaxis and navigation across steep gradients of nutrients or toxins, and (iii) assembly of communities in heterogeneous nutrient-toxic environments. Such an application is also applicable in bioremediation screens, rhizosphere research in crops, and early identification of antibiotic-synthesizing strains.

How come not to imagine real soil?

Direct imaging usually disturbs the sample or disrupts any native gradients, which is counterproductive. A chip will allow pore architecture to be reconstructed on demand, on top of placing gradients, and yet, optical access is not lost. The implication of that in practice is repeatable experiments and statistics as opposed to one-off observation.

How does it actually look, and what can be adjusted out of it?

Although the designs can differ, the majority of soil-on-chip systems comprise: a transparent network of microchannels and a mimesis of a labyrinth of pores; flow inlets and outlets as well as an inlet channel and reagent flow; and stagnant regions where stable gradients are achieved. You regulate the flow rates, nutrient levels, and even the geometry of the so-called soil by selecting alternative microstructures, straight channels, complex cavities, and mazes as baseline motility, as habitat complexity, respectively.

What are the benefits of microfluidics compared to the conventional culture assays?

The headliners are transparency in NA microscopy, reproducible geometries, and built-in gradient generators. Not the least is the small volumes (fast diffusion, minimal reagent consumption) and that it is possible to multiplex conditions on a single chip – dozens of habitats simultaneously instead of a single flask.

Is a soil-on-chip applicable to anything more than simple science indeed?

Yes. In the case of bioremediation, screening of degradation consortia under realistic transport constraints is achievable. Authentic root-proximal ag-microbial gradients placed in ag can be imitated, and colony behavior can be measured. In the case of natural product discovery, confined co-cultures in heterogeneous chips have the potential to induce natural product secondary metabolism that cannot be induced on flat agar plates.

What would MIC do to bundle a Horizon Europe proposal in this topic?

We usually assume microfluidic architecture, a rapid prototyping and automation of the experimental process, and we aid exploitation planning at the beginning. Notably, the presence of a high-performing SME fortifies a consortium: according to our experience working on several European consortia, projects involving MIC achieve success rates about 2× the official average. It is a result of combining strict engineering and proposal optimization work packages, interlocking with lack of credibility work packages, believable schedules, and demonstrators.

Do you provide feasibility or just prototypes only?

We deliver both. Usage: Embodied balanced microstructures based on proofs of concept. Reimbursable substantive alpha platform (material, and bonding optimised to imaging and flow classes)- Application-tuned beta assay units with tests. partners are provided with a full, testable setup, including extra incubators or gradient modules as required.

Biological model already exists. So, what information can you begin with?

Countless levers with a very small stick: desired gradients (molecules and ranges), target organisms and target media, imaging, and maximal shear, target throughput (runs per day). Preliminary pore-scale images or rheology data are useful as it aids us in mapping biological constraints to microstructure selections at a quicker rate.