Lab-on-chip for high-throughput fungicide screening: MAHT-FunSST

Author

Sehrish IFTIKHAR, PhD

Publication Date

April 30, 2019

Status

Keywords

fungicide screening

Lab-on-a-chip

fungal pathogens

fungal spore encapsulation

antifungal efficacy testing

crop-protection industry

agricultural disease control

Your microfluidic SME partner for Horizon Europe

We take care of microfluidic engineering, work on valorization and optimize the proposal with you

Fungicide screening is stuck in an innovation gap, which incurs staggering expenses and takes a long time to market.

Furthermore, resistance to fungicides is challenging, requiring sensitivity screening and recalled fungicides.

Lab-on-a-chip for fungicide screening: introduction

Fungicides have become an integral part of agriculture for efficient food production.

The loss of a fungicide through resistance is a problem that affects us all.

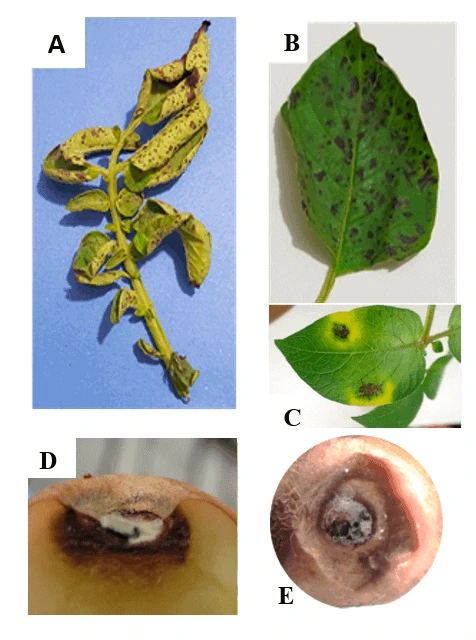

Recently, early blight (EB) (Alternaria spp.) appeared with increasing frequency in European potato fields and occurred in Africa, America, Asia, and Australia.

Several fungicides are sprayed to control the disease, and resistance against EB fungi has been reported.

Scientists study fungicide sensitivity on cellular, organismal, or field levels to understand fungicide distribution better and effectively manage the resistance.

Also, a baseline sensitivity should be established before new fungicides are launched. The conventional techniques to screen fungicides and to identify the resistance are time-consuming and laborious.

Lab-on-a-chip for fungicide screening: project description

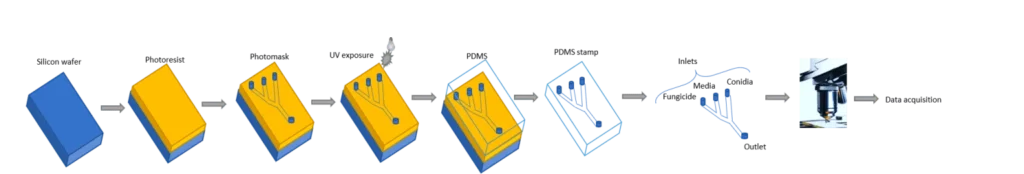

To perform fungicide screening and baseline sensitivity testing, microfluidic lab-on-a-chip with multiplexed cell culture chambers can emerge as an efficient platform compared to conventional agar and high-density healthy plates.

Microfluidic lab-on-a-chip has been developed in many fields since they have numerous advantages compared to traditional screenings, such as low reagent consumption, manipulation of cell number and density, monitoring of a high spatial and temporal resolution, and observing the dynamic behavior of many cells. Furthermore, new insights into fungicide mode of action can be obtained.

Lab-on-a-chip creates a uniquely accurate method for observing the biological responses, providing a more comprehensive analysis that could ultimately revolutionize how fungicides are developed and how to control the development of fungicide resistance in fungi.

One of our primary objectives is to establish a simple microfluidic lab-on-a-chip to perform high-throughput (HT) fungicide screening studies into droplets.

Fungal spores will be encapsulated individually in droplets produced on chip, germinated and grown, and finally in contact with fungicides.

Elveflow OB1 pressure controller will allow precise control of the flow rates of each liquid and the controlled encapsulation of fungi and fungicides.

For more details, feel free to have a look at Sherish’s review on microfluidics for fungus identification!

This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 MSCA-IF under grant agreement No 843162 (MAHT-FunSST).

Researcher

Dr. Sehrish IFTIKHAR

Research Associate

- PhD in Agriculture Plant Pathology (University of the Punjab, Pakistan)

- Master of Science in Agriculture Plant Pathology (University of the Punjab, Pakistan)

- Bachelor of Science in Agriculture Plant Pathology (University of the Punjab, Pakistan)

Areas of expertise:

Agricultural plant pathology, fungicide discovery and design, fungicide screening, fungicide resistance and sensitivity, molecular microbe-plant interaction

Check our Projects

FAQ – Lab-on-chip for high-throughput fungicide screening: MAHT-FunSST

What problem did MAHT-FunSST solve?

Traditional agar plates and microtitre-based assays are slow, reagent-intensive, and ineffective for comparing large numbers of compounds, doses, and isolates, which is precisely the need in resistance management. The MAHT-FunSST fills this innovation gap by enabling rapid, concurrent sensitivity testing and creating robust baseline distributions prior to the commercialization of a new fungicide.

What does the chip practice do?

Monodisperse spore droplets are produced on the chip. These microreactors contain nutrients and, at the same time, the fungicide, in the exact amount needed. To set droplet size, spore occupancy, and exposure timing with precision, each inlet is controlled by an OB1 pressure controller to stabilize flow rates. The growth, germination, and inhibition are then observed directly in the droplets.

What were the biological models and use cases that were prioritized?

The platform was modeled on phytopathogenic fungi used in field resistance monitoring, such as early blight (Alternaria spp.), the rising prevalence of which in European potatoes has made monitoring sensitivity vital. This is equally true of other crop pathogens in which stewardship is based on good baseline information and regular re-evaluation.

Why is droplet-based LoC superior to plates in making baseline sensitivity curves?

Three leverages: (i) statistics – a large number of independent microreactors per run; (ii) fidelity – close regulation of the number of spores, exposure time, and gradients; (iii) signal – direct monitoring of germination and growth dynamics on a high spatial/temporal resolution. Reduced compound will yield cleaner EC50/EC90 estimates and a narrower confidence interval.

What are the outputs of the platform?

Examples of common such outputs include: dose-response curves between isolates, baseline sensitivity distributions prior to market introduction, relative potency rankings of candidates, and time-resolved inhibition profiles (which can hint at a mode of action). The data is inherently structured for downstream modelling (e.g., resistance shift detection).

What is the technology maturity, and what is the appearance of a deployment?

The project provided an operational PDMS chip and a procedure for controlling flow via pressure and displaying readouts via imaging. Practically, you will require: a chip, a pressure controller, standard microfluidic connectors, a microscope (or compact imager), and an analysis pipeline. In terms of the technology readiness, it lies between applied research and prototyping and is relatively easy to customize to a specific crop/pathogen panel.

Is it applicable outside the fungicides?

Yes. The design – single-cell / single-spore encapsulation, controlled co-flow, and multiplexed exposure, also applies to bactericides, biocontrol agents, synergist effect studies, and formulation effects. Persistence and post-exposure regrowth, two important properties of resistance management strategies, can also be probed using the same chip layout.

What of the quality and reproducibility of data?

The flow is stable, with pressure used to generate droplets; over-dispersion is reduced by loading single spores; and lanes with identical microenvironments are appropriate for comparing the results of a run to one another. Due to low reagent usage, you can experiment with more doses, which statistically stabilizes the parameter estimates without excessively increasing costs.

What is the possible role of MIC in my consortium since MAHT-FunSST is over?

Two levels. To science: we will scale the MAHT-FunSST roadmap to your organism, chip format, and screening logic, and provide you with a functional prototype with assay validation. To fund and implement: MIC is an experienced R&D-SME partner; our involvement usually significantly increases proposal success relative to official averages, and we focus on scale-up, automation, and technology transfer. In brief: Squiggly experiments, cleaner data, and an increased Horizon Europe bid.

Do you exclusively have droplet-based designs?

No. Other fungi or endpoints show better responses in chamber-based culture with continuous perfusion (e.g., longer exposures, morphological measurements). We are as likely to alternate between droplet and chamber designs as we are to have them in the same apparatus, where they can have a sale at your expense.

What are the common limitations or traps?

The two most widespread problems are spore clumping and surfactant compatibility; both can be addressed with upstream filtration, short sonication, and tested surfactant/oil systems. Imaging throughput is an issue, too – automated stage control and batch analysis do not allow this to become the bottleneck.

Can MIC become an R&D-SME partner and co-develop the platform at our call?

Yes. Microfluidic engineering, as a scientific automation technology, is essential to MIC in chip design and microfabrication, flow control, assay integration, and prototype delivery. We are also members of various European consortia, where we are active and assist with proposal writing, impact, and exploitation planning.